Reflections on Thinking as Language

Two years of using LLMs regularly has challenged a strong belief of mine: that fundamentally, thinking is primarily just language that happens in our heads.

I’m aware that this wasn’t a prevailing view in psychology, but I still want to talk about what changed my mind, since it didn’t require reading academic literature – just engaging with practical tools and reflecting on the experience.

How I Thought the Wrong Thought About Thought

I developed my previous view mostly through self-reflection. The thoughts I’m aware of are basically just sentences, or at least clauses. I consistently hear a voice, or maybe a shadow of a voice, narrating my reasoning and reactions. There are probably a few exceptions, but not many that I’m aware of. I learned that the name for this phenomenon is subvocalization, and I feel it even more strongly when reading text.

When I started getting interested in subvocalization, I asked friends about their experience and some claimed not to have an internal voice. Over time, I came to think it was more likely that they just didn’t notice the voice than that they didn’t have one at all.

I came to this conclusion partly because I’m much more language-oriented than average, so I have a hard time even imagining thoughts without voice. And I might have been somewhat right: apparently, some studies suggest that subvocalization is key in reading and becomes more obvious as the difficulty of the material increases1… so maybe everyone is doing it to different degrees, sometimes at such low levels that it isn’t detectable.

This view of thought, as fundamentally composed of words, made me extremely bullish on LLMs. With more and more computation and training data, I couldn’t see why they wouldn’t ultimately replicate the skills of humans. Even creativity seemed achievable, since a great deal of creation is the random-ish recombination of ideas from different domains until landing on something good.

The main challenge I could imagine was the lack of a up-front thesis before generating lower-level thoughts. As I understand them, most LLMs just produce one word (well, token) at a time and then repeat – sort of meandering though the sentences without knowing where they’re going.

That’s not quite how thoughts work in my head though, since often I formulate a goal or thesis and then begin fleshing out the component thoughts to support it. However, “chain of thought” models (e.g. OpenAI’s o1 and o3 models) seem to have addressed this by having the LLM generate high-level commands before breaking down each one, which more closely mirrors the way I feel myself thinking.

Changing My Mind About My Mind

There are some pretty obvious objections to this view. One is that we clearly don’t need to compose paragraphs for every situation. We often make snap judgements and plans without taking time for mental monologue.

For example: while proofreading this post, I saw a typo. I switched windows, ran a Find command for the misspelled word, updated it, and switched back to my proofreading window all in under two seconds. There just wasn’t enough time for me to have said to myself: “Looks like I misspelled ‘conclusion’. I should return to my editor now, find the misspelling, delete it, retype it, and return to the original application.”

To me though, I feel like what’s happening in situations like this is a lot like the invention of new words for concepts that come up often. Just as we now have the word “brainrot” to more concisely describe a concept that would have taken many words to explain before, I think we develop shorthands in our heads for common strings of thought and strings of actions. I’ve never dug into this idea and it may well have been debunked, but it seems at least plausible. When I found a typo, I thought “fix misspelled ‘conclusion’” and my brain was familiar enough with that phrasing to translate it into actions.

But the much stronger objection – and the one that has convinced me – is that language ultimately doesn’t capture the essence of the world, only the context we need to pass between us. It is not itself a full representation of reality, since we all have a pretty clear grasp of that reality in our internal selves and we developed language only to pass messages among different people who already share that grasp. I struggle to articulate this clearly, but it’s more obvious with examples.

We can try to describe arithmetic addition in language. Indeed, I thought for a while that a linguistic description was fundamentally no different from understanding addition itself. But that’s not right, because we can verify how addition works by actually doing it in the world.

We can execute 2 + 2 by setting up two sets of two objects and combining them, which produces four objects. We actually teach children this way: showing them examples of executing math in the world so that they grasp what math is doing, not just how to answer math questions in the abstract. Eventually they build a good enough mental model that they can execute the problem in their heads without physical props, and then memorize the answers to common scenarios.

Higher level math is harder to execute mentally, but the point is the language we use to describe math is not math itself. Math is an encoding of reality, and the correct answer to a math problem is defined by how the world behaves in a certain situation. We could try to answer math questions purely based on linguistic patterns, but it would be analogous to a calc student who never understands the fundamental theorem of calculus2: they might learn patterns well enough to answer many questions, but novel applications would stump them. They’d be limited by how much a given math problem resembles ones they’ve seen before.

This is in contrast to strong mathematical thinkers, who might actually see new ways to solve a problem because they can grasp the underlying real situation that math describes, and potentially reformulate it in an equivalent (but more easy-to-solve) way.

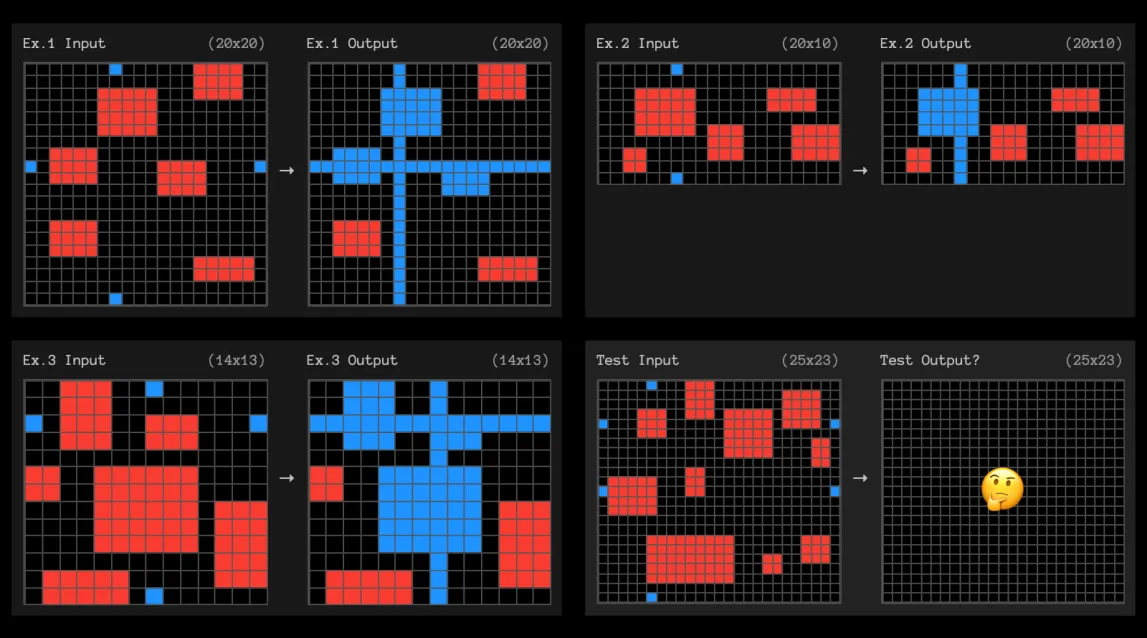

This article on OpenAI’s o3 model contains a great example of a problem that’s easy for humans specifically because we don’t need to think of it in words.

Barring some breakthrough, an LLM will continue to be a calc student who memorizes patterns, but an extremely good pattern-memorizer. It’ll remember any problem construction that’s ever been on the internet, for any kind of math problem, and be able to solve it. But it won’t be able to solve new kinds of problems, because those definitionally haven’t been solved or decomposed yet.

We may yet address these limitations in LLMs through the addition of multi-modal layers (i.e. processing of some non-language representation), and I think that’s already happening. But grappling with them has helped me learn about humans: while we are highly verbal creatures, our brains use more than just language.