Too Good To Be True?

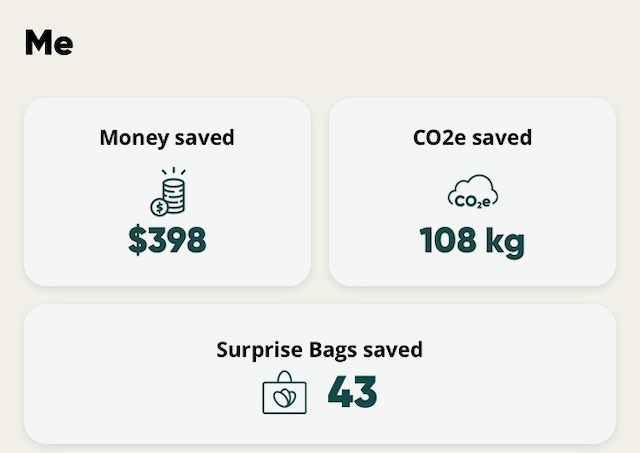

The Too Good To Go app has been my fixation this summer. Since moving to a new neighborhood two months ago, I’ve picked up 43 surprise bags (all the more absurd because I didn’t discover the app until two weeks after moving). Dramatically increasing my consumption of sandwiches and pastries wasn’t in my original goals for the summer, but here we are.

Too Good To Go lists “bags” that restaurants will sell you at a steep discount, though their contents will be a surprise. You may get a basic description (“grocery bag”), but no more, and you have to reserve the bag well in advance, then arrive in the specified time slot – which is often pretty tight.

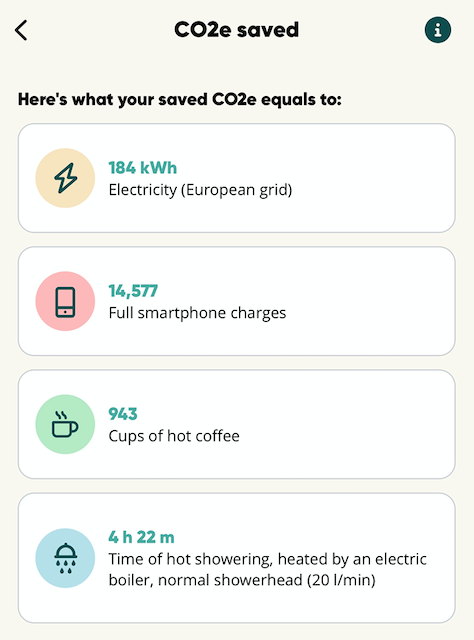

The app leans strongly into the idea of reducing food waste, implying that your purchase of food is having an environmental impact. The time slot offerings do indeed suggest that this food would not be sold otherwise; they typically are scheduled for the last hour or so that the restaurant is open. You can find a dashboard in the app that displays the money you’ve saved side-by-side with the carbon dioxide equivalents you’ve “saved”. Calculating both of these is a dubious endeavor, since I wouldn’t have bought the food without such a steep discount, and the surprise bags aren’t strictly replacing food I would have eaten otherwise – I’m not eating croissants as a substitute for dinner (well, usually). Still, I’m happy to be told that I’ve offset the amount of emissions generated from making 943 cups of coffee, since that’s probably about the number of times I’ve used my aeropress this summer.

Honestly, there’s a good reason I’ve used the app so much: it’s a great deal and a ton of fun. I’ve tried Puerto Rican and Cuban restaurants for the first time, received a random assortment of fruits from a grocery store, and sampled more boutique donut varieties than I knew existed. The thrill of the chase is more than half the fun; the food is good and cheap, but a reason to bike a few miles through the city (especially as someone who spends all day working at home) is just a really pleasant addition to my life. I’ve found restaurants and even neighborhoods that I probably would never have visited.

Despite the fact that I’m going to keep using the app one way or another, on many bike rides I find myself wondering about how the app changes restaurant behavior, and through it, net food waste.

One idea would be that it doesn’t: restaurants buy and prepare as much food as they would have made without the app, and if demand is lower than they projected, they list the extra inventory on TGTG. In this scenario, all the food you get via the app would have otherwise ended up in the trash (or taken home by employees, or perhaps donated elsewhere). But I think this is unlikely. The ability to reclaim some revenue from “extra” food would change the business’ incentives, as an economist would point out.

Imagine I sell biscuits, which cost me $2 to make and which I sell for $5. On 60% of days I’ll get 8 customers buying a biscuit, but 20% of the time I’ll have 7 customers and 20% of the time I’ll have 9. Any extra biscuits I haven’t sold by the end of the day are thrown away.

If I prepare 7 biscuits, I’ll make $21 today ($5 * 7 - $2 * 7). If I make 8, it gets more complicated. 80% of the time I’ll have at least 8 customers and make $24 ($5 * 8 - $2 * 8) and 20% of the time I’ll only sell 7 and waste one, for $19 ($5 * 7 - $2 * 8) – for an expected profit of $23 ($24 * 0.8 + $19 * 0.2). If I make 9, it’s even more complicated: 20% of the time I sell 7 for a $17 profit ($5 * 7 - $2 * 9). 60% of the time I sell 8, making $22 ($5 * 8 - $2 * 9). 20% of the time I sell 9 for $27 ($5 * 9 - $2 * 9). My expected profit when making 9 biscuits is thus $22 ($17 * 0.2 + $22 * 0.6 + $27 * 0.2).

| Biscuits Baked | Expected Profit | Average Biscuits Wasted |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | $21 | 0 |

| 8 | $23 | 0.2 |

| 9 | $22 | 1 |

With these projections, I would maximize my profit by baking 8 biscuits. Yes, I sometimes wouldn’t be able to fully meet demand, but baking extra biscuits means paying for their materials but not necessarily getting any revenue from them.

Now let’s say I start participating in Too Good To Go, where I can sell extra biscuits at $2 apiece. Even at that low price, which is just the cost of materials for me, it changes my calculus. The previously-wasted biscuits can now be salvaged. Let’s say I keep making 8 biscuits a day, and redo the math – but it’s easier math now because we can just omit the excess biscuits from our formula, since they generate exactly as much revenue ($2) as they cost to make ($2). So 20% of the time I sell 7 biscuits at full price and 1 on TGTG: $21 ($5 * 7 - $2 * 7). 80% of the time I sell all 8 at full price: $24 ($5 * 8 - $2 * 8). Average profit: $23.40, a slight improvement over our previous $23.

But what if we were to bake 7, or 9? Well nothing changes in our calculus for 7; we still sell all 7 biscuits at full price 100% of the time. 9 is trickier, but a shortcut is to just add back the cost of the wasted biscuits. We wasted an average of 1 biscuit when we produced 9, which means we’d recoup $2 using TGTG, bringing our expected profit to $24. Our options look like this now:

| Biscuits Baked | Expected Profit | Average Biscuits Wasted |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | $21 | 0 |

| 8 | $23.40 | 0 |

| 9 | $24 | 0 |

We’re making more money at both 8 and 9 biscuits produced, but suddenly our profits at 9 have leapfrogged those at 8. So now we’re going to start baking more biscuits.

Especially at larger numbers of biscuits, even if the TGTG price were below cost of goods, it would still make sense to produce more once there’s an opportunity to sell extra food. And this suggests that smart restaurants are probably making more food than they would have otherwise.

It’s an interesting result, but not surprising when you step back. You are, essentially taking less (or no) loss on inventory that isn’t sold at full price. If there’s little downside to producing more than is sold, you might as well prepare enough food to meet the maximum likely demand. Now there are some simplifications here that ignore real world considerations: making food requires not just cost of inputs but also labor time/expense. Also, there’s no guarantee that every TGTG bag will sell, so the expected value of extra inventory is slightly below the price at which it’s sold. But even so, the ability to sell some excess food at a discount affects restaurant incentives and always encourages them to prepare more.

Does this mean that the app isn’t reducing food waste? As long as the food you get from Too Good To Go results in you eating less other food (even if it’s not an equal reduction), then I don’t think so. Restaurants are likely making slightly more food than they would otherwise, but not so much that it offsets the salvaged food – if you look at the numbers above, even when assuming TGTG fully pays for cost of production (and I think that’s not likely), it has a fairly small impact on the quantity produced. I haven’t toyed with adjusting the assumptions to confirm that’s always the case, but my intuition is that it would be.

Now you can buy 6 donuts for $4 and feel no regret. Well, no more than the regular amount of regret.