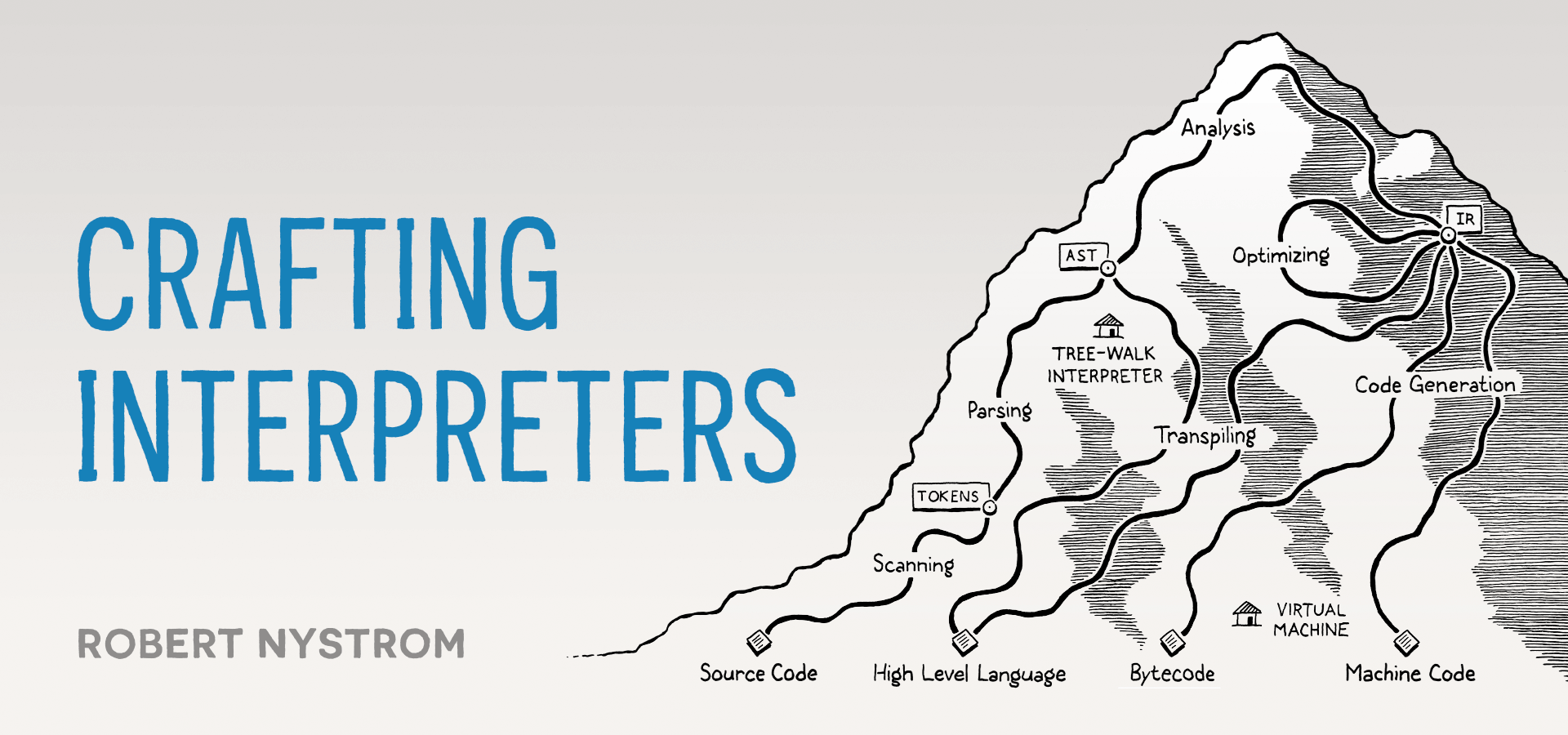

Crafting Interpreters

In January, during some time off between jobs, I started working through Crafting Interpreters by Robert Nystrom. I think I originally discovered the book via r/ProgrammingLanguages. There aren’t that many accessible books for programming language design and implementation, so discovering the book (and that it was free to read online!1) was very exciting.

It’s an absolutely incredible book, in which you learn about programming languages while implementing your own. The author describes himself as having been “bitten by the language bug years ago”. I would say I was bitten by the language bug sometime last year, mostly as a result of getting deeper into the mechanics of Python’s interpreter implementation. For most of 2021 I followed the python-dev2 mailing list, where I lurked and consumed a lot of technical discussions that I mostly didn’t understand. By the end of the year though, I was understanding more and more, and I was getting really curious about what it would be like to design and build a programming language myself.

I’m nowhere near the level of skill (or time commitment) needed to creating a new language, but Crafting Interpreters has been such a fun time. The book is divided into two parts: in the first part you’re shown how to build an interpreter in Java3 for a toy language called Lox, and in the second part you build a compiler for the same language using C. Lox may be a toy language, but it supports “garbage collection, lexical scope, first-class functions, closures, classes, and inheritance”, so you get a sense of what it would be like to create a “real” programming language.

Back in January, I made it about halfway through part one, and then took a break once I started my new job. Over this last week, I’ve had the time to jump back in and have been having a great time. I’ve finished with variables, basic operators, conditionals, and functions; what remain are mostly the trickier – but more interesting – features.

The book provides you all of the Java code necessary to build the interpreter, which is nice (since you’ll definitely be able to get things working) but also means it’s easy to fall into passive code-copying.

My strategy has been to follow along with the Java code in each section, and then to reimplement the same functionality in Python on my own.

So I have two GitHub repos, jlox and pylox, but obviously I’m a lot more proud of the latter.

Rewriting the application in a higher-level language has been a very satisfying exercise. One of the first things I noticed was how handy Python’s recently-introduced pattern-matching functionality was for numerous pieces. For example, the interpreter module (distinct from the full interpreter application, which is composed of scanner, parser, and interpreter modules) receives code from the parser, and at that point the code is represented in an abstract syntax tree, a nested hierarchy of statements and expressions. Statements can contain other statements (or expressions), and expressions can contain other expressions. But the particular subtype of statement/expression encountered is what determines how to execute it, and unwrapping the components within the statement can make that much more compact. Take the method to execute a statement:

def execute(self, stmt: Stmt) -> None:

match stmt:

case ExprStmt(expr):

self.eval_expr(expr)

case FunctionStmt():

function = LoxFunction(stmt)

self.environment.define(stmt.name.lexeme, function)

case PrintStmt(expr):

result = self.eval_expr(expr)

print(stringify(result))

case VarStmt(token, initializer):

value = self.eval_expr(initializer) if initializer is not None else None

self.environment.define(token.lexeme, value)

case WhileStmt(condition, body):

should_loop = self.eval_expr(condition)

while should_loop:

self.execute(body)

should_loop = self.eval_expr(condition)

case BlockStmt(statements):

self.execute_block(statements, Environment(enclosing=self.environment))

case IfStmt():

self.execute_if(stmt)

case _:

raise RuntimeError

Here, the statement is passed as an argument to the method (stmt), and then passed into a pattern-matching block.

Depending on the type of stmt, we want to take different actions in order to execute it.

We can unpack the internal components of the stmt using the arguments after the subclass names in each case – so case VarStmt(token, initializer) actually stores the stmt’s token attribute in a variable called token and its initializer attribute in a variable called initializer, both of which we can use within the following block.

A VarStmt is something like var x = 3, so extracting variable name (the “token”) and the initial value makes it simpler to evaluate the initial value and then store it in a variable named with the given token – which is exactly what the two lines in the case VarStmt... clause do.

That feature may seem a bit niche, but when I started this project I didn’t really understand the benefit of pattern matching. I knew that some other languages supported it4 and that some people were excited about it, but I didn’t see much applicability in my own work. Building an interpreter was such a new problem that I wasn’t able to reflexively reach for programming patterns I was already familiar with, or at least I was less likely to do so.

Obviously, most of my learnings from the book so far are about interpreters and compilers, not Python language features. One takeaway that’s really stuck with me is how much simpler things are with stateful code. Which is kind of funny, actually, because I’ve been told that pure functional languages like Haskell are good for parsing. Maybe they are in the abstract, but I suspect that it would be very hard to add good error reporting in a purely functional approach. It seems like tracking errors – both in order to report their location and to accumulate as many as possible before failing in earlier stages, like parsing and scanning – requires keeping track of a lot of state.

I, a noob, didn’t see this coming. I read the early chapters, built my Java scanner and tokenizer in classes, and then implemented my Python versions as free-standing functions. I scoffed at the foolish verbosity of Java, forcing users to write classes when they’re totally unnecessary.

Unfortunately, in this case, they are actually quite necessary.

So much so, in fact, that chapters later I had to migrate my (now fairly large) scanner and tokenizer into classes in Python.

Many relics of the functional approach remain: every function in my parser takes in two extra arguments that could have been entirely omitted if I’d accepted the usefulness of state from the beginning.

These are tokens and current_pos (current position), which I use to track how far along the parser is through the input.

That means each function also needs to return a new current position along with its regular output, and my forgetting to overwrite the current_pos variable has led to at least half the bugs I’ve found in my parser so far.

Lesson: use state for your parsing from the beginning, keeping the input, your current position, and any errors in instance-level variables.

While I’ve probably written more than two thirds of the necessary code for the interpreter, I still have a lingering itch to refactor the Python implementation. It just feels like I’m not taking full advantage of the benefits of a dynamic language. My pattern-matching exploits were fun and helped me avoid implementing the Visitor Pattern (which is how it’s done in Java), but I think if I sat down and reconsidered the architecture, I might come up with some more simplifications. That said, I’m a bit wary of straying too far from the beaten path; doing that is exactly why I had to go back and OOP-ify big modules of code. So maybe I’ll finish the full interpreter and then try to do some refactoring.

This has been one of my most serious side projects in years, and by far the closest thing to a college course that I’ve taken since, well, college. Finishing the full book by the end of 2022 is ambitious but achievable. It’s been a ton of fun and I will likely write at least one more post later in the process.

-

I’ve since acquired the physical copy as well, mostly for my bookshelf. But it’s a book that is so nice in so many ways that I sometimes switch to it for the occasional sections that don’t require writing code. The author’s graphical design and typography sensibilities definitely show. ↩︎

-

If you happen to be interested in following Python’s development, python-dev is no longer the place for you. New discussions mostly happen on the Python Discourse. ↩︎

-

Thus ending my incredible five year stretch of being a professional code-writer in industry without ever writing a line of Java. Regarding the end of the streak, I want to apologize to my all my fans out there for letting them down. I compromised my values, and I’m not proud of it. In the future I will complain about Java even more as an act of contrition. ↩︎

-

Scala seems to be the one that comes up most. ↩︎